If there is romance in skateboarding as a lifestyle- and there must be some, right?- then the idea of making it, Rocky style- must be part of it.

When skateboarding as we know it today was in its comparative infancy in the 1980’s, a trickle of (predominantly European) skateboarders made their way to California to try and make a living from skateboarding- which at that time all but necessitated contest entry.

As home cinema promoted California (in skateboarding, San Francisco specifically) and the leisure economy boomed in the 1990’s and into the 2000’s, more talented dreamers from around the globe would inexorably find themselves drawn to what was then the skateboarding industry heartland, hoping to piece together the cheap rent, sponsor-juggling path to earning a living through skateboarding.

On any given day in San Francisco, Slap magazine photographer Joe Brook could drive around the city without a plan and pull up at any of the city’s then-endless skatespots and shoot kids from all over the world going for broke.

If they were lucky- and they were by no means all lucky- some of those kids would have had somebody from back home who had already got a foot in the door and held it open for them.

The Spanish certainly looked out for one another in LA, and likewise the Brazilians- as they always do for each another.

But what about the kids that came from skateboarding nowheres?

It takes an unreal amount of self-belief, or nothing to lose, to rock up in a foreign country and try to make it in an industry with zero safety net and where somebody will take your place for a rucksack and a pair of Globes.

Chany Jeanguenin made it through just that fire.

Not only was he one of the top European skateboarders of his generation, he was also one of the best-rounded ever, equally adept at street and vert.

That is highly unusual anywhere- but to do so coming from Switzerland was absolutely unheard of.

To do all that while skateboarding was morphing day-by-day, makes it even more unfeasible.

From coming up through the sponsorship ranks to turning pro, and then working in the industry opening doors he’d had to kick open for himself, Chany did the thing.

He actually made his dream come true against all odds.

You have to be more than just talented and more than just hungry for that to be said of you in the skateboarding game.

With that kind of impeccable skateboarding history, it can’t be too much of a surprise that Chany recently took up the role of Park Coach for the Swiss national team.

We thought now would be an opportune moment to take a sweep back through history with one of the people best positioned to discuss without sentiment the past, present and future of skateboarding which he has witnessed firsthand.

Friends: Chany Jeanguenin.

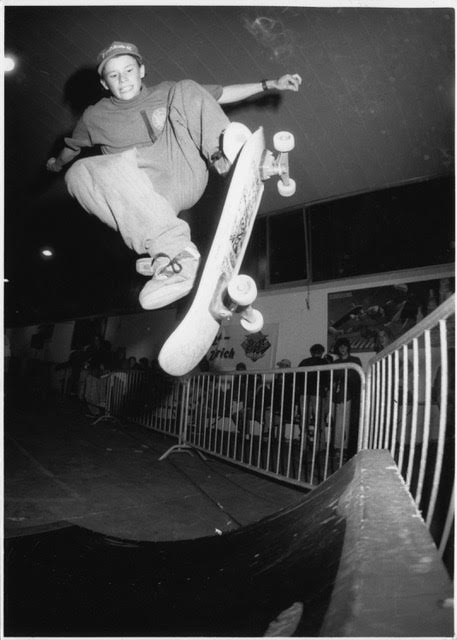

Ph: Thomas Gentsch/ @gentschybaby

Can you talk to us a bit about your skateboarding life in Europe before you decided to try your luck in the States?

Skateboarding in Europe, or Switzerland specifically, wasn’t very popular back then, but nonetheless, we had some good contest series and demos where everyone gathered to share their skate knowledge.

It was always really fun to meet all the Swiss riders from different regions of the country and see how the level was progressing. We had a small vert scene, but the level of skating was actually pretty good, and it was motivating.

The European vert skating scene, in general, was actually very strong and healthy

Ph: Paul Heuberger/Vertical Skateparks Switzerland

Could you explain to us just how hand-to-mouth that existence of being a sponsored foreigner trying to come up in the US at that time was?

It was definitely a tough time for most European skaters. Many European riders struggled to be valided, especially during the San Francisco Embarcadero days—it was probably the most critical moment in skateboarding, even for American skaters who showed up there to try to break through.

I was riding for Real Europe at the time, and honestly, I’m not sure why, but I felt like I got a pass on the harshness, and I was quickly accepted into the scene.

Who’s floors did you sleep on?

I crashed on the floors of Joe Brook, Dave Metty, and Greg Hunt, and later with Ocean Howell and Mark Wyndham.

How different was the lifestyle of pro vert skaters to that of pro street skaters at that time? Who had it better?

One thing that hit me hard, and that I didn’t quite get the memo on in Europe, was that vert was basically dead. It was all about street skating, there were no much vert ramps left around. That was a tough reality check for me and my come up at the time.

Vert was fading fast, and a lot of the vert skaters were struggling—they were trying to make the transition to street skating as best as they could. Even Tony Hawk ended up selling his house and retiring for a while.

Street skating was definitely a better option if you wanted to make a living from skateboarding, and it was also considered a lot cooler at the time. But even as a pro street skater, making a living was still very challenging.

Ph: Paul Heuberger/Vertical Skateparks Switzerland

You were one of the very first professional skateboarders- besides that sort of half-hearted adidas v1 semi-team- to be tapped up as someone who could introduce mainstream sportswear brands into skateboarding. Now they are pretty much holding the sponsorship sky up. What can you tell us, there?

At the time, riding for Converse felt like new territory. Corporate shoe sponsors had already been part of skateboarding since the early days, but they ended up getting replaced by skate-focused brands like Vans, Airwalk, Etnies, and Duffs. Converse came back by working with Guy Mariano, and then they approached me for another run. That period was a really nice and unforgettable chapter of my skate career.

We got to travel across all continents, connecting with people all over the world—sometimes not even necessarily within the skate community. We did a lot of demos at schools and random events across Asia, for example.

Since the brand wasn’t run by skateboarders, we faced some challenges in marketing and product development, but we still had a few really solid years. Unfortunately, just when things were starting to really come together, they filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

Do you consider your Transworld ‘Modus Operandi’ part to be your definitive career moment?

I think it was a very important moment—a hugely influential video. Being part of it was an incredible blessing.

Thank you again to Transworld, Ty Evans, and Jon Holland. But for me, it was a bit bittersweet. I had a few injuries at the time that really shook me up, and I wasn’t able to finish my part the way I wanted to. So in a way, I always see my part as unfinished.

Still, I’m proud to have been part of it.

As we mentioned earlier the sponsorship landscape is very different now from then. What happened?

It’s very different now. I was responsible for sponsoring a lot of riders during my time with Expedition and Kayo Corp, and even back then, we were already seeing the big shift in marketing and sponsorship: social media was quickly replacing print, and we had to balance between performance and popularity when making sponsorship decisions.

Today, that line is even more blurry. Contest results are easy to understand, and the popularity of contests has kept growing within skateboarding and among the general public—everyone understands the results.

That’s why I believe contests play the biggest role in skateboarding sponsorship and in generating money at the moment.

Given that pro skateboarding is at its most unstable since the Big Pants Small Wheels era*, do phenomena like the World Skateboarding Tour provide an alternative lifeline for skaters who want to make a living from it?

Yes, as I mentioned earlier, I think it’s the best way to make a living in skateboarding and gain recognition—if you can make it to the top. Of course, it’s not easy to do, and we hope it’s not the only reason skateboarders approach skating.

It’s absolutely incredible how consistent and impressive skateboarding has become in competition. But we also know that contests are just one outlet to showcase skateboarding. We hope the creativity of video parts, the freedom of expression, skateboarding talent, and style will always be present and recognised—because skateboarding can’t only exist within competitions.

Let’s hope the next generation doesn’t become only contest skaters, and that sponsors will continue to recognise street skating as a very important part of skateboarding culture and sponsorship.

Ph: Alan Maag/ LAAX

Can we talk a little bit about your Swiss compatriot Oli Buergin’s contribution to skateboarding in Europe?

Oli was very important to me growing up. We skated and competed a lot together, especially on vert and mini ramp, which weren’t as popular as street skating. We learned from each other and pushed each other.

He became a key figure in European skateboarding, both skating and working for Sole Tech. He was one of the top skaters in Switzerland and Europe, and he managed to skate and work in the industry his whole life.

Oli played a huge role in the growth of skateboarding by organising European skateboarding competitions for… a few decades now, maybe.

He has been involved in many other contests and skatepark building projects. His contributions to the European scene, through both his skating and his work, have been incredible.

Ph: Thibault Le Nours/ LAAX

What are your hopes and ambitions for your new role with the Swiss national team?

For me, it’s very clear: the goal is participation in the 2028 Los Angeles Olympics.

However, it’s not an easy road, especially with our small team and limited access to proper bowl infrastructures.

We have a good level and great motivation in street, which is awesome, and I hope to develop the same energy and potential in park, which I’ve just started to coach.

We’ll see how the next few years unfold, but I always believe that anything is possible.

- skateboarding's 1992 cultural nadir